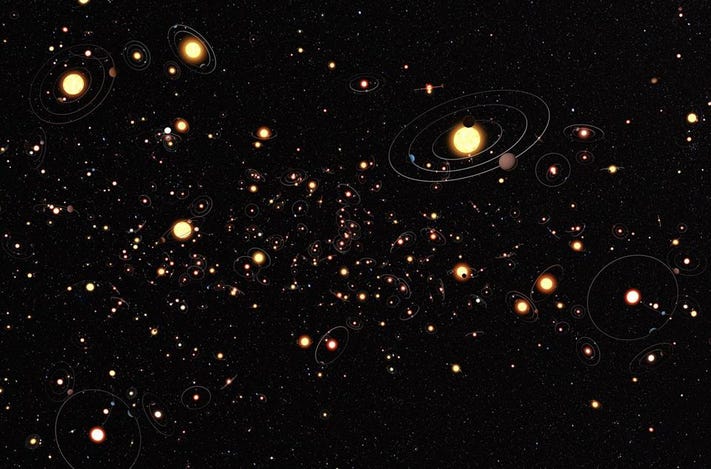

Indian astronomers have found a new method to understand the atmosphere of a planet beyond our solar system by observing the polarisation of light. In our search for life beyond Earth, science has taken us to over 5,000 exoplanets within the Milky Way galaxy, which are rich in water and atmospheric compositions, some bigger than Earth, others even bigger than Jupiter.

Astronomers from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics have now designed a method to study the atmosphere of these planets by observing polarisation signatures or variations in the scattering intensity of light using ground-based radars and observatories. Exoplanets have been discovered to be revolving around a star just like planets in our solar system revolve around the Sun.

The reflected light of planets orbiting these stars would be polarised and unveil the chemical composition and other properties of the exoplanetary atmosphere. In a paper published in The Astrophysical Journal, Aritra Chakrabarty and Sujan Sengupta detail a three-dimensional numerical method and simulated the polarisation of exoplanets.

The two astronomers in the paper state that just like planets in our solar system, exoplanets are slightly oblate due to their rapid spin rotation. Further, depending on its position around the star, only a part of the planetary disk gets illuminated by the starlight. This asymmetry of the light-emitting region gives rise to non-zero polarisation.

They developed a Python-based (programming language) numerical code that incorporates a state-of-the-art planetary atmosphere model and employed all such asymmetries of an exoplanet orbiting the parent star at different inclination angles and calculated the amount of polarization at different latitudes and longitudes.

The polarisation at different wavelengths is sufficiently high and hence can be detected even by a simple polarimeter if the starlight is blocked. It helps study the atmosphere of the exoplanets along with their chemical composition.

Aritra Chakrabarty, who is a postdoctoral researcher at IIA and co-author of the study said, “Even if we cannot image the planet directly and the unpolarised starlight is allowed to mix up with the polarised reflected light of the planet, the amount should be a few ten parts of a million, but still can be detected by some of the existing high-end instruments such as HIPPI, POLISH, PlanetPol. The research will help in designing instruments with appropriate sensitivity and guide the observers.”

Astronomers largely use the transit method to detect planets far away in other systems. A transit occurs when a planet passes between a star and its observer.

According to Nasa, transits reveal an exoplanet not because we directly see it from many light-years away, but because the planet passing in front of its star ever so slightly dims its light. This dimming can be seen in light curves graphs showing light received over a period of time. When the exoplanet passes in front of the star, the light curve will show a dip in brightness. If this process repeats on a pattern it confirms a planet-like object is orbiting the star on a path.

Ministry of Science and Technology in a statement said that the polarimetric method can detect and probe exoplanets orbiting with a broad range of orbital inclination angles.

Leave a Reply